INTERVIEW

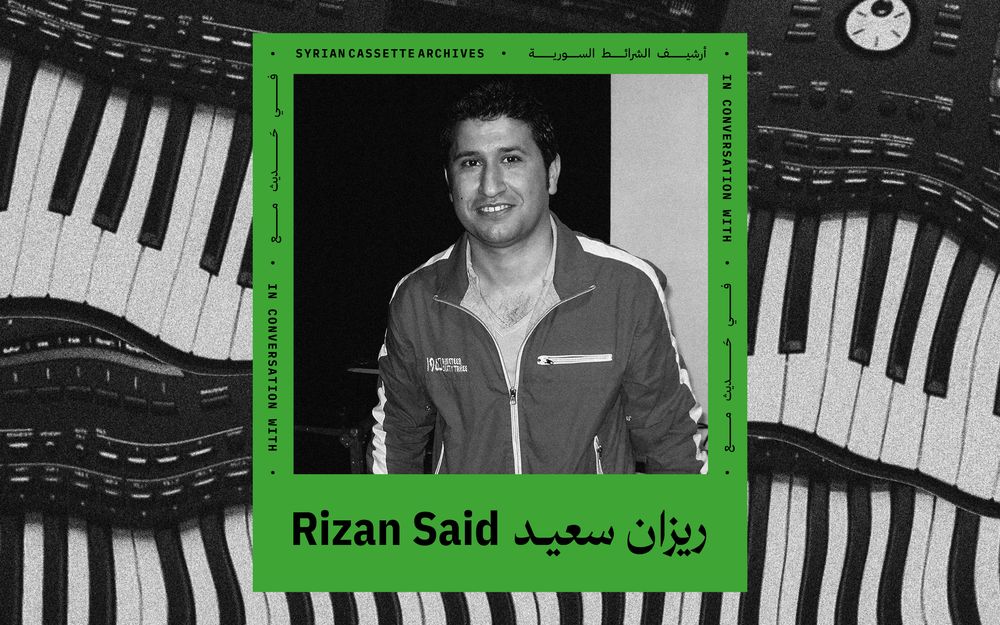

RIZAN SAID

In Conversation with Syrian Cassette Archives

Rizan Said is an internationally renowned Kurdish keyboardist from Ras-Al-Ain, Syria. He has collaborated with, performed alongside, and composed for numerous Syrian singers, most notably Omar Souleyman, with whom he crafted a distinctive sound in the mid-1990s and later toured internationally. An early prodigy on the electric keyboard in northeastern Syria’s Jazeera region, his signature sound was prevalent at weddings and cassette releases throughout the 1990s and 2000s. He continues to compose and produce music for regional singers, as well as for television and film, in addition to releasing his own solo works through labels such as Annihaya Records, Discrepant, and Akuphone. In this discussion, Rizan provides a personal perspective on the musical histories of Hassake, the emergence of the keyboard and cassette in the region, and his own experiences within the Syrian music circuit during the cassette era. Rizan Said Links: King of Keyboard LP (Anniyaha Records) Saz û Dilan LP (Akuphone Records) Instagram Facebook SCA / Yamen Mekdad : Rizan, we are pleased to be doing this interview with you. You are a vital part of the Syrian Cassette Archives project, with your history and expertise with Syrian music – specifically music from northeastern Syria. Rizan Said: You’re welcome, my brother. Yamen: Could you please introduce yourself for the people who may not know you? Rizan: Welcome, my friends. My name is Rizan Sa’id Al Issa. I was born in 1978. I’m from the Hassake Governorate in Syria, from the city of Ras Al Ain. I’m a musician – primarily a keyboardist. I’m also a music producer, and I perform as a solo musician at festivals. I have composed and recorded songs for many singers. Yamen: Can you tell us about your childhood? What was your relationship with music, and when did it begin? Rizan: Well, it all started when I was in the sixth grade, when I began playing music as a hobby. My father made me a reed nay (a kind of flute) to encourage my interest. I also used to listen to music often on my cassette player as a child. Eventually, I began participating in my school’s annual Al-Ruwad music competitions (local, regional and national competitions to find top talents in all fields, from science to sport and arts). In the first year, I participated using our school’s flute (a recorder). The following year, I played the accordion and the flute, which meant I participated twice during fifth and sixth grade. I think I started to play the flute in grade five, and then by grade six I was playing complete songs. So, you could say that this was the beginning of my musical life. Yamen: Does your family support you when it comes to music? Rizan: For sure. If your family doesn’t support your interests, you can never succeed. It has happened to me and to others. If your family doesn’t strongly support you, you will fail and won’t have the same passion to continue. Yamen: In those cases, you don’t take it seriously. Rizan: You don’t take it seriously because of that lack of encouragement. Yamen: So, you started playing the flute when you were around 11 years old? Rizan: I started playing the flute first, but I didn’t really know how to play it well, I was just intrigued by it. Yamen: Then one step at a time, you made progress? Rizan: Yes, in sixth grade, I started playing the flute and accordion properly. In grade five it was like…how can I explain? Like a kid just playing randomly on the flute. They encouraged me at school and asked me to play in the competitions, for example. Yamen: And how were you introduced to the accordion? Rizan: My father’s friend had a small accordion at home, and he lent it to me to practice on. I also played saz and buzuq at the time. Every Kurdish house had a buzuq, they were widely available. Yamen: Is there a big difference between the saz and the buzuq? Rizan: They are different – how can I explain it? There is a difference in the sound. The saz sounds more Kurdish and Turkish than the buzuq. Buzuq is known for its ability to play Arabic songs more than the saz is, for instance, in the songs by Fairouz. So buzuq has a closer relationship to Arabic music in that sense. The saz has a longer neck. The musical notes are the same for both, there’s no difference there. Yamen: Do you have more freedom with the musical scales? Rizan: Yes, you have longer strings and more frets. There is also the bağlama (a variation of saz) that has more notes and different fretting. It has its own specific way. Yamen: What was your personal experience with the first cassette you owned – as a listener rather than a musician? Rizan: From the time I first came into this world, we’ve had cassettes and a tape recorder in our house. For example, we had wedding cassettes. Wedding cassettes had something new, something nice. As a kid I loved that those cassettes had music – they had arrangements, they had life in them. I mean, at one time when I was a kid, I didn’t listen to them because I necessarily wanted to enjoy the music. I just wanted to know what the tape contained. Yamen: What was the first cassette you remember? Rizan: The first... There was this Kurdish singer, his name is Feqiyê Teyran, otherwise known as Nîzamettîn Ariç. When he first started, he had an academic career. Maybe you’ve heard of him? When he first started working, he gave birth to the same concepts we are thinking about now – developing the styles of music that I want to work on. He started 30 years ago, working and creating his own style, man! When you hear him you don’t know if it’s a soundtrack or singing or art. I’ve been listening to him since those early days. I met him two years ago in Germany. I told him I’d loved him since I was a kid. You know what I mean? He is old – more than 65 years old. But brother if you listen to his albums, you’ll know there is something unique in his work. I loved him as a kid and I still love his albums. Yamen: Could you tell us more about the ethnic and cultural diversity in the Ras Al Ain area and your experiences growing up there? Rizan: For sure. It was there that I learned how to play Arabic music, Mardelli music (related to Mardin, Turkey) and Turkish music – and I played Iraqi songs as well, for example. In places like these, you learn many different colours of music. It wouldn’t have been the same if I’d lived in Damascus for example. Growing up in that town, I learned about and was exposed to the many different cultures from the area, music included. Yamen: Would you meet musicians and singers from different cultures? Rizan: Of course, definitely. There was a border between us and Turkey, but Turkish cassettes were sold everywhere. Generally, they used to listen to Turkish music a lot in our area. A lot, my friend. And they listen to Iraqi music more than Syrian music, because our area is closer to Iraq and Turkey. Yamen: What about Kurdish, Syriac and Armenian music – were there cassettes available in your area from these different cultures? Rizan: I’d never heard Syriac music, honestly, or even Armenian. I heard that Syriacs listened to Mardelli, because Syriacs spoke the Mardelli dialect. So when they have parties they sing Mardelli and Kurdish songs. And the Kurdish dancing was an important part of their weddings. Armenians loved their songs and their own language more than Syriacs. They used to circulate it between themselves, but we didn’t have that kind of cultural exchange between us. You know what I mean? I heard Armenian songs later, only in the last few years. I listened to it and found that it’s very close to Kurdish. Especially the Duduk instrument. It’s so close to Kurdish. One important thing about Syriacs was that I used to know Syriac hymns – church hymns in the Syriac language. There was this priest, a father. He was my friend, and he used to visit my house sometimes and sing some of these hymns in the studio. He sang Syriac songs for us, which were also very close to Kurdish and Mardelli songs. Yamen: How did you develop your career after participating in those national talent competitions that you mentioned? Rizan: After that… There’s a young man who is a friend of mine, and who is (singer and composer) Mohammad Ali Shaker’s nephew, Hussain Shaker – Yamen: Of course, he is well known. Rizan: He saw me by chance when I was playing the flute and accordion. He was a chess teacher, and a judge in the chess section of the Al-Ruwad competitions. The room where I was performing was right next to the room where Hussain was evaluating chess competitors. After I finished, he called me in and asked if it was me playing the flute, I said yes… The important thing is we got to know each other, and he became a mentor. He’s a musician too, so he took me under his wing. He told me, “My brother, there is an instrument called the electronic keyboard which will be very popular soon…” You know, people like him who were older knew better about these things – they knew that keyboards were the instrument of the future. Yamen: What year was this? Rizan: 1993, I think. Yamen: And through him, you were introduced to the family, and started playing with them? Rizan: Yes, our families knew each other already since we live in a small area. They often greeted my father in the market. But after he got to know me, we began visiting each other often. I was so young then. I was always the youngest person there. They used to encourage me – and when an artist encourages you, it’s totally different. Eventually, he introduced me to his uncles, Mohammad Ali and Mahmoud Aziz Shaker. Hussein told me, “We have an album coming up, and we are trying to find you a keyboard so you can accompany us on it.” But there was no keyboard… Yamen: You weren’t playing the keyboard back then? You only played the flute? Rizan: And the accordion. Come to think of it though, the accordion is almost like a keyboard. So, Hussein said, “Brother, we’re going to the cultural centre to try to borrow the keyboard from them.” Back then, the manager of the cultural centre was a man named Muhammad Jazzaà. He is Kurdish. He told Hussein, “That’s perfect brother, we need more musicians. In this case, take our keyboard.” Hussein said, “We need it for around a month, so Rizan can practice for the cassette we’re recording, then we’ll return it to you.” Yamen: And whose album was it? Rizan: It was Hussein Shaker’s album. Yamen: Can you describe your first experience with the keyboard? Rizan: Honestly, once I played it I fell in love with the keyboard. It felt like something from the future, and that’s what I wanted. The techniques we had back in those times… I mean, we never knew about something called a chord, for example. Of course, we used to hear these beats and chords, or a bass guitar and an electric guitar on the cassettes we’d listen to. When I turned on the keyboard and heard those things right there, it used to make me so happy. You know what I mean? Yamen: Yes, of course. Rizan: So then I loved the keyboard, but we didn’t own one! So next, we bought a small Casio keyboard. Yamen: Where from? Rizan: We asked someone to bring it back from Beirut. At that time there were Syrian soldiers serving in Lebanon. We asked a soldier from Ras Al Ain who was stationed there to buy one. He brought it back with him when he visited home on leave. Yamen: Nice. Was it expensive back then? Rizan: 6000 Syrian Pounds (SYP), as I remember it. Yamen: A serious amount of money back then. Rizan: Yes. Then, after we bought the keyboard, I joined the band. Yamen: What was the band’s name? Rizan: Kom Abohar – meaning Spring Band. In Kurdish, Kom is band and Abohar is spring. The band was led by Muhammad Ali Shaker back then. Yamen: And you continued working with them, playing and recording and doing concerts? Rizan: Yes. We recorded (and produced) for the people in the area who had no recording capabilities. We would record everything on a normal (two-track) cassette deck. We would call this the recording deck. Eventually, Hussein Shaker decided to form a band that could play at wedding ceremonies. This was in 1995. Over time, we developed and were able to buy a more modern keyboard – a big Yamaha. I accompanied Hussein on keyboard at his concerts. At the same time, my friend Omid (Hamid) Suleiman had begun playing buzuq in a local group that he had formed. So I’d also accompany Omid at his performances during times when Hussein had no work for me, since he didn’t have a keyboard player. Yamen: You were the only one? Rizan: Yes. At that time, keyboards weren’t very desired as instruments. People only wanted to hear darbuka and buzuq. And when we would play keyboard, people initially didn’t accept its sound. Yamen: How did people react? Rizan: Little by little, the people got used to it. Yamen: But what did they used to say? Why didn’t they like it? Rizan: They just didn’t like it. They didn’t accept its sound. They said, “It sounds like a horn”, “It sounds like a whistle”. They didn’t like it. But one step at a time, they got used to it. The younger generation, that is. Older people didn’t like it. But the younger generation came to love it. Yamen: Let’s talk about recording. The first cassette release that you were featured on – who did you record it with? Rizan: At that time, I didn’t know how to arrange music. I didn’t know a thing. They’d tell me to play a certain way, and I would play it. I would do only what they instructed me to do. You know what I mean? Back then, I was playing concerts accompanying Hussein Shaker, and also Omar Souleyman, who was then a new singer on the scene. He didn’t have a proper group, and always worked with different musicians. So up until the end of 1996, I spent two years working between Hussein, Omid and the Kurdish guys. We were busy with live recordings and events, recording sessions for the Kurds, for Omid, for Hussein and for Mahmoud Aziz Shaker. These were all live shows, sort of like jam sessions and nighttime concerts we did during those two years. That’s how I learnt the ropes. After I started working with Omar Souleyman, I bought Korg keyboards and the GEM WS1. The Korg was western. It had accordion sounds. It had the sounds of the zurna, but not the same sound as the zurna we use here. I would then modify its sound through programming. I used to really love keyboard programming and creating new sounds. Yamen: How would you program it? Rizan: By using effects in the keyboard. Since I was young, I’ve loved spending evenings with the keyboard, working on programming effects. I managed to get the zurna closer to the actual zurna sound. I’d manipulate the keyboard’s electric guitar factory preset to do this. I would reprocess and manipulate those guitar sounds to make them sound like a tanbura, using effects such as chorus, phasers and flangers. I’d also experiment with making the sound monophonic, to try and make it sound more like a buzuq. So, with these modifications, I created new sounds. For instance, I brought the sound closer to that of a buzuq. Live buzuq used to be a part of every wedding concert. With the keyboard, I cancelled that. When we showed up to a party, we would only bring a keyboard. And by the time I started working with Omar Souleyman, we had reached a point where people didn’t accept a concert at a party without a keyboard. Especially Arabic parties: “Why did you only bring a buzuq and a darbuka!” Yamen: When did that happen? Rizan: This was by 1998 or so, when people stopped accepting buzuk and darbuka alone. There had to be a keyboard. And by the early 2000s, 2001 or 2002, if I didn’t accompany Omar at a party, the people objected. We had made a name for ourselves together. We made something unique – something special, in our own style. I’m not saying that we were musically strong or anything, but with this specific style we created, we were in high demand in the area. Yamen: Can you tell us how you went from working with Hussein Shaker to Omar Souleyman or Omid? And when did you start concentrating on your own business? Rizan: Honestly, working at Arabic parties was more profitable than the Kurdish ones at that time. It brought in more money. So Omar asked me, “Rizan, why don’t you work with me?” I saw that he had more work on offer than the other guys. I also love to work on developing a style. I love to play music. I mean, just to work, just to go out there! So I agreed, and went with Omar. One step at a time, we built something together over time, creating a song here and a song there. As I said, we created our own specific style. What made it better is that I did it with the keyboard. I mentioned before how I owned a tanbura, for instance, and a saz – I had these real instruments at home and knew how to play them. But this new style I’m talking about was all developed using the keyboard. Then, with the Korg’s sequencer, I learned how to record and arrange. Little by little, I would construct tracks inside the keyboard. Around that time, I wasn’t working with Hussein Shaker as regularly – only if there were parties. But he was familiar with recording and engineering, and he told me he had bought a new device – a four-track cassette recorder, which recorded instruments on four separate channels, unlike our previous two-track recording deck, which could only record all the instruments live simultaneously. He said we could use it to work together recording and producing music for people. Ours was a Fostex four-track back then. So with this equipment, we worked together for a while, producing different artists, using my keyboard, arranging and recording music with Hussein’s mobile studio. Using the sequencer, I began recording and arranging everything inside the keyboard. There were 16 tracks inside the keyboard’s sequencer. I would record and arrange internally, then put the results on one of the four track channels along with the singer’s voice. This would leave us with three more tracks to work with. Yamen: Perfect! Rizan: And after that time, computers showed up. When computers came, it widened the field. Over time we tried to develop ourselves. It all happened step by step, it didn’t happen by just doing things randomly. I mentioned that since my youth, I loved developing new sounds. During my early collaborations with Omar Souleyman, I told him I’d like to try some new directions. I told him I wanted to compose musical interludes to include in our live shows, and that If he liked what he heard me playing during the concerts, he should immediately go over and speak to the poet. Back then, Omar would go down and mingle with the dabke dancers and sing from the floor while I stayed on stage. We’d agree on something, and he'd understand me. I told him if he heard a melody I played during the party – one that he liked and thought worked well – then at that moment, to go approach the poet in attendance, and invite him to come up with some lyrics for what I just played. During these concerts, I would know immediately if Omar liked what I was playing, because he would start singing along to my improvised melody. Yamen: Where would he bring the lyrics from? Rizan: A poet is always with him when playing dabke at weddings. Omar never goes to a wedding without a poet. Yamen: Why? Rizan: Firstly, he doesn’t read or write. Second, he likes to have a poet with him so he can properly address and sing to the people attending the wedding. Or, for instance, if a guest asks for a personalized song about themselves, the poet can help with that. And third, there is a benefit if you sing about a specific person. You’ll get compliments, for example. So after that, he got used to working with poets, and realized that they are essential from an artistic point of view. They helped us create a lot of songs. If I played an interlude that works, the poet could immediately improvise lyrics for it. Most of Omar Souleyman’s songs that you can hear from that time originated with these interludes I created. Yamen: OK, so you would compose and play a melody on the spot, and the poet would come up with lyrics immediately? Rizan: When I’m onstage and see that the people are getting into some serious dabke dancing, I play improvised interludes. Something that sounds like tarararan tararara… I’ll play an interlude like that to heat up the dabke, because I see people are dancing well and really going for it. At a time like that, for example, Omar senses what’s working well melodically and asks the poet: “Write lyrics for what Rizan just played – He made me go crazy… tararara… tararara… I loved it”. We had this special bond. We would usually record all of these parties automatically, and each of these became cassette albums. So when we released these party cassettes, other singers would listen to what we’d done and replicate it at their own parties and on their cassette albums, and that’s how it became famous. Yamen: Ok, so about the cassettes. The first cassette release that you played on was with Hussein Shaker? Rizan: Yes, true. Yamen: When did that happen? Rizan: This was in 1993. Yamen: Can you tell us about how you recorded cassettes back then? Did you have cassettes at home? Rizan: We had cassettes. I mean, this was the norm then. My father used to bring cassettes to the house and we’d listen to them. You could find cassettes and a cassette recorder in any home. Yamen: And what was the process of making recordings? Where were you recording, and how did you record? Rizan: We used to make recordings in a house. We’d meet in an empty house with no noise, far away from the street. At that time there wasn’t a specific place to record or a room designed as a recording studio. We used to go and hang out somewhere and record. But we would set the mood – making sure there were no kids around, for example, and using a house that wasn’t directly on the street, because if a car passed by during recording, you’d have to stop, rewind and go back five, ten or even fifteen minutes to record everything over again from the top until you finished. We’d find a suitable place to set up our equipment and tape recorder, and start recording. That’s how it was. Yamen: And after the first cassette was released, how was it received in the market? How were the cassette sales? Did you record it for your own benefit, or for a production company? How did you sell it to the market? Rizan: No, back then, there weren’t any production companies to deal with. We recorded the tapes ourselves and then used duplication machines locally in Ras Al Ain. For instance, I believe back then Hussein made 100 or 150 copies this way. He used a photographer to print his photo for the front cover and distributed the tape by hand. It was done like that in those days, as a kind of promotion. Yamen: Who did he distribute them to? Rizan: To his friends and colleagues. It wasn’t like nowadays. Before recording companies came, it used to be done this way, as promotion or encouragement. For instance: today, I give my album to someone as a gift. They then gift it to someone else – and even if they don’t, at least I gave them the album as a gift. So we continued gifting, gifting, gifting, until the production companies started – and then all of those early methods faded and segued into how it is today, where you record the album, send it to the company, then the company sends it to an agent, and it gets distributed to the market. It depends on the artist’s luck whether he sells or not. At that time, the only person who used to take money from companies in our area was Omar Souleyman, because his cassettes were successful. The company would tell our agent: “Send us any new cassette by Omar and whatever amount of money he wants, he’ll get it. We want to be the only company with the first copy – exclusively – and no one else gets a copy of it.” I mean, there were no copyrights, and no strings attached. For instance, If Omar were to give them the promise of an exclusive, but then also give the album to someone else, he would put the company in a very bad position. This is how it used to go. Yamen: And what was the second cassette you worked on? Rizan: I think it was for Muhammad Ali Shaker. After that I worked with Omid (Suleiman). These were all pre-computer recordings. I recorded them on the cassette deck and the four-track. Yamen: And they would make 150-200 copies of each tape, financing it themselves? Rizan: Yes, they used their own money to record. Everything was done for free. We even recorded everything for free. Yamen: Do you mean that these were more like cassette advertisements for your party concerts? Rizan: No, we did these out of love. Before, there was this sort of love between us my brother. We didn’t even think about money between artists when we were working for someone. But after Hussein Shaker bought the four-track, and we got a more modern keyboard, Hussein said, “Brother we bought this equipment, so let’s at least charge our friends when we work for them. We bought this stuff and we are working hard for them.” So, we started taking a small amount of money, like 1500 to 3000 SYP, for example. That’s how it was back then. That’s after we started recording with the four-track, ha! Before the four-track, we took nothing for the live recordings. After computers showed up, I started taking money, but it was just a token amount. It wasn’t that big a deal. Yamen: Got it. So when recording, you would play each instrument independently, then put them together on the four-track? Rizan: Yes. Hussein used to combine them on the four-track. I mean, it was so basic. Unlike computers, where you can control 100 tracks, and control the arrangement for example. After 2004, and with the song “Khataba” (recorded with Omar Souleyman) things started to progress. We got more familiar with the process, we learned more. We started considering everything we did – if we were creating a new song, we wanted it to be better than the last, because now we were now under the spotlight, and had started working at an international level. Step by step, as the circumstances changed, we progressed. Yamen: What do you mean by international? Rizan: I mean in the past, for example, we used to work solely on a domestic level. We’d play at a local party, an album would get recorded onto cassette that day, and by the next day, the people who attended the party could buy the cassette. It could sell in Hassake, in Qamishli, or to some other singers. They used to buy Omar’s cassettes and listen to them to see what he was singing and then sing like he did, since he was a hit at that time. In the early days, the cassettes didn’t sell outside of Hassake, Deir Ez Zor and Qamishli - never. After the song “Khataba” became popular, Omar spread across the whole country, for example via satellite channels. Yamen: Which channels? Rizan: There used to be a channel called Al-Thahabia (Golden Music). In the beginning, they used to show folk songs from the coast, Daraa, Suweida, various regional areas. Yamen: And so you became nationally known through that? Rizan: Yes. And through that channel, our songs were also broadcast outside Syria. Yamen: Outside the governorate, or outside Syria? Rizan: Outside of Syria. Al-Thahabia channel was Saudi. Its base was in Egypt and it belongs to Saudi Arabia. Yamen: How did that affect your cassette recording and sales? Did you then start working in a studio, or was everything was still happening on a computer? Rizan: No, back then I had a home studio. In 2004 after we did Omar’s song “Khataba”, and up until 2009, I used to make 6 to 7 songs a month. Because “Khataba” was such a big hit and I composed it, work started coming in like crazy! I’d work for this artist or that artist – an artist from Aleppo, an artist from Raqqa, an artist from Deir Ez Zor, an artist from Qamishli, an artist from Damascus... Of course they were all folk music singers. So I did a lot of work from 2004, after “Khataba” and the song “Shkther Mshtaq” for singer Ezzedine Al-Furati. Yamen: You composed that song too? Rizan: Yes I composed it. Yamen: In your opinion, how did cassettes generally change your work or the work of artists around you, once they appeared on the market and started spreading? Were you aware of this era as it was happening? How did it affect the fame, the workload and the musical production? Rizan: It became something else after I started going to concerts and things became more professional. I started listening to more cassettes. I started listening to wedding cassettes, old artists’ cassettes. Half of the artists I listened to are also collected by Mark (with Syrian Cassette Archives) – like Abdulqader Sulaiman, Said Yousef and Salah Rasul, for example. Those were the people who used to sing in weddings – I would listen just to hear what they sang at a wedding, what they played at a wedding for example, so that I might benefit from the performance, be inspired, and get clues for what to play myself. I mean, later I started listening to the cassettes I liked for work and as a professional. Yamen: And from a work point of view, since those cassettes were the sole method of publishing and advertising, how did this affect not just your work as an artist, but let’s say economically as well? Rizan: Economically... I told you that our cassettes were strictly local. All of them were local, and never went outside the governorate. If it happened, it didn’t pass the areas of Deir Ez Zor or Raqqa. So the cassettes used to bring us our work. We’d be invited for a wedding in Deir Ez Zor or Manbij, or sometimes to Aleppo. If it weren’t for the cassettes, no one would know about any artists from our area back then. Yamen: How did cassettes affect musical work in general? Before the advent of cassettes, people used to travel to Damascus or Aleppo to record, which was a big deal. After cassettes came into the picture, it allowed anyone to form a group, to record, duplicate and sell cassettes from home. How did this affect everything? Rizan: Don’t forget about the quality… The production work and the techniques when you recorded in Damascus were never the same as homemade tapes. Just to keep it in context, I mean. Not even 20% of the quality, the work and the technique of those studios. I mean, we performed during a night out and recorded it. It was more like a form of publicity. Those recordings were not professional, like we were seriously working. It’s like, we were friends having a jam session, casually putting things out. Even the recordings weren’t done professionally, we were just working earnestly as friends. We didn’t have it in mind that, Oh God, this song is going to turn out like it is now. It wasn’t a dream of creating something, having it become popular and reaching a global audience. Back then, we didn’t think of it in this way. We were simply a gang, brother. A group of musicians who loved music. We loved to record something and put it out there so people could listen and give us their opinions, for example. Our goal was never to be famous and go somewhere with it. This was how we used to think back then. Yamen: After the changes at that time, and with your home studio, how would you transfer the recording from the studio to a cassette? Where did this process happen? Or did you stop recording cassettes and start making CDs? Rizan: By the time we started working on a computer in 2004, it was all digital and sold on CDs and DVDs. Yamen: And how did the process of arranging music happen? Rizan: By that time, recording companies were responsible for this. When satellite channels appeared in the mid-2000s, not a lot of people made complete albums. They would make a song at a time, just to give it to a satellite channel. Everything costs money. If we recorded an album, it would cost us around 100,000 SYP back then. So, no – they’d say “we’ll record one song and make a video clip for it.” That cost at least 150,000 SYP, but at least the whole world could watch it on satellite. So that’s how work started being done, and how it continued. Yamen: So going back, between the time of your first cassette release and the time you established your home studio, could we discuss how the industry worked? Were those tapes distributed inside and outside Syria? Rizan: No, all were inside Syria. If it went outside Syria, for instance, to Saudi Arabia, it was by those who worked in Saudi Arabia or Kuwait and came to Syria for a visit. They took albums back with them and listened to them at home. So if a Saudi guy heard it, or a Kuwaiti guy heard it, it got famous. But not officially, where for instance a company in Aleppo would distribute to Saudi Arabia – there was nothing like that then. Yamen: Did you and the artists you worked with used to sign contracts with the production companies? Rizan: Before getting the computer, I had nothing to do with the companies or the business side of things. When a singer asked me to work with him, I would. He would release the album, and I had nothing to do with it. After computers, companies started dealing with us, asking us to produce albums and mediate between the singer and the company. For instance, a company might ask me if a singer like Saad Harbawi had made a recording, whether I could check the album out and see if it was good, or if Harbawi might agree to a release. So we became mediators in this way, since we had a studio and we arranged and produced for many artists. For example, Abo Abdo Al-Hafez – the owner of Sawt Al-Hafez records in Aleppo – was always in touch with me. He’d ask: “Hey Rizan, is there anything new from Omar or Saad? Is there any new artist around you that you think could be a hit? Anyone that we can record or release?” That’s what happened. Yamen: And how would they agree on things? What was the wording? Rizan: It depends on the artist. Companies wouldn’t release just any new artist. They would only release cassettes for big artists they knew would sell. If a new singer approached a company with their cassette, the company would tell him, “Brother, we can duplicate your cassette, but you have to pay for 100 of them to cover costs.” Yamen: And they’d copy 200 cassettes and give him 100? Rizan: No, they only give him 100. He pays for and receives 100 copies of the cassette, if he’s unknown and doesn’t have a following yet. But if the singer is up-and-coming, he provides the tape and they duplicate and promote it. Got it? Yamen: By promotion, do you mean they cover production costs and distribute the cassette for the artist? Rizan: The company make 200 copies, and charges the artist to cover the costs. They create the cassette cover, the artist gets 100 copies for promotion, and the company sells the other copies through their stores and distribution channels. That’s for a normal emerging artist who doesn’t have much of a name yet. But if it’s a famous artist who works all the time like Saad, like Omar, or like Adnan Jaburi, the company would pay them money to take the album. So back in 2003-2005, shaabi singers of that league could take 100k SYP as a net profit from the company. Back then, that was around $2000 USD. Yamen: But the singers would pay production fees from their own pocket? Or would they use the studio for free? Rizan: So for instance, I could be paid something like 10, 15, 20 thousand to record for them back then. Yamen: Ok, and the other musicians? Rizan: Usually it was only the singer recording. No musicians. If they needed a musician, they’d pay and arrange it, I had nothing to do with it. That’s how it was. Yamen: Back then, you concentrated on working with Arab artists, those three in particular – Omar, Jaburi and Saad – who used to sell a lot of cassettes. Were there also Kurdish artists? Rizan: I worked a lot for Kurdish people. I worked for Omid Suleiman, Mahmoud Aziz Shaker, Muhammad Ali Shaker. I also worked for Roni Jan and Hisso, I worked for Nowruz bands. There was a lack of available musicians and good equipment – for example, you wouldn’t find microphone, pickups, cables… they didn’t have the capabilities. So a month before Nowruz, I’d provide a service to record their songs, so that when Nowruz came round, they only had to do the dubbing. They’d hold the microphone and sing with the music. And if they couldn’t sing well with the music, we’d record the music with his voice and he’d only lip-sync onsite. Yamen: How was the situation in the area regarding Kurdish songs? Were there any problems recording Kurdish songs in Syria or Turkey? Or was that not a concern you faced in the area? Rizan: There weren’t any problems as long as the songs weren’t patriotic. Nothing was forbidden but the patriotic music. Songs that had Kurdistan’s name or any patriotic name. Regarding Nowruz – political songs were prohibited, which was normal… Yamen: Nowruz songs were permitted or prohibited? Rizan: Wallah, look, it depends… Nowruz depended on the activities you did that day. For example, if the host of the event spoke a few words out of line, if he said a few words that hit a sore spot, he would ruin the whole party from beginning to end. For example, if a song contained lyrics or topics that were prohibited, that would also ruin the whole party from beginning to end. But if the party went on without these things, nothing would happen to stop it. Aside from this, around 2005-2006 I travelled to Damascus, which is when Mark (Gergis) met us. At that time, I got to know a big studio in Damascus and worked with Majed Zain Al Abdin, a well-known man and musician. He composed for Ruba Al Jamal and Asala Nasri. I had a studio that burned – I’d built a studio in Damascus, but in 2006, it burned down in a fire along with my house. So some friends of mine in Damascus tried to find another place for me to work. They took me to Mr. Majed Zain Al Abdin – I’m sure you’ve heard of him. He wrote the lyrics and composed the song Saabha Tesab Hawnha Bthoon (If You Make It Hard, It Will Get Harder, and If You Take It Easy, It Will Be Easy). He had a huge studio, and I worked there. Part of his studio was designated for a distributor that worked with Spacetoon (Pan-Arabic children’s TV channel), while another section was just for his own use. And within that space, he prepared a station for me, and brought in all the equipment I needed. At that time, I knew more musicians like Rudwan Nasri, Tarek Turkan Al Arabi, Sameer Kusaibati. Yamen: Ah, you worked with them? Rizan: I didn’t work with all of them, but I worked with Rudwan from among that group. Maher Ghalaini was among those that worked with Spacetoon. We were all in Majed’s studio – each in a separate room. Yamen: And what did you do there? Rizan: Mr. Majed told me, “Brother, your situation is like this now with me – and you are from the Jazeera region right?” At that time, back in 2006-2007, I was mostly working with Kurdish and Turkish styles from my region. There was nothing like that in Damascus. They were listening, and wondering how I was playing tanbura on a keyboard, or saz on a keyboard! “How are you playing the zurna on a keyboard? What are those beautiful songs? They sound Turkish!" Those songs sounded Turkish to them – that’s all they could hear. You know what I mean? Yamen: Because they weren’t familiar with it. Rizan: Yeah. That’s exactly why Rudwan Nasri had this TV series called “Husrom Shami”. This series had to include Turkish-style music. So I worked with him on that series. Yamen: So you were working for Zain Al Abdin’s studio? Or you worked there for your own benefit? Rizan: No, no – Mr. Majed told me: "Because your studio burned down, I want to give you a room. Find your clients, and when the work and the songs come to you, take the money, and whatever you want to pay me, is fine." Yamen: I see. Rizan: The man was an artist. When one is an artist, he feels for others, and can help them out when something tragic like that happens. This was the way of Mr. Majed. He told me “Brother, just work and take your time. If you get work, pay me whatever you want – and if you don’t, you can stay here and pursue your hobby.” So that was our arrangement. Yamen: What work did you do there? Rizan: I was introduced to Vahe Demirjian. I used to visit him. He gifted me a soundcard for my system when he heard my story. You must know of Vahe Demirjian? He is a well-known musician in Damascus. The best pianist in Syria. Of course he is old, he is sixty years old now. He is very well-known. Yamen: Did he used to play with the institute? Rizan: No, he had a recording studio in Mezzeh, Damascus, where I worked for a while with the Iraqi musician Karim Hameem, who is the father of Aseel Hameem (a popular Iraqi singer). Yamen: Who did you record with in these Damascus studios? Rizan: I mainly worked with Karim. He had agreements with Jordanian and Gulf companies. Any good quality folk or shaabi music from Syria, he would work on and would collaborate to distribute them in Jordan and the Gulf. He needed a producer of shaabi music, so I worked with him on that. I would also do my own work for Adnan Jaburi, and for Omar Souleyman. I also worked for another singer, whose name I can’t remember now, and I worked for a singer called Omar Al Shaar. I also produced for Hussein Al-Salman, a Jordanian singer who is known now as the royal family singer. That’s how it happened. A lot of things have happened to me, and sometimes I get them mixed up, but that’s how it all happened. Yamen: Cassette-wise, with the cassettes you were a part of, what was your experience with publishing and copyright at the time? Rizan: Now, publishing and copyright happened after, I think, 2000 or 2001 – something like that. There were copyright laws for only 6 to 7 months in Syria. They were serious about it, but then it got out of hand. Yamen: Before, there was nothing with copyright laws? Rizan: No, no, even after the copyright laws. There was a law which lasted, as I told you, six to seven months only, and then it got out of hand. The strongest evidence is when Mark visited Damascus, He found the cassettes in Al Abaseein Garage. On the floor. Basically, it shouldn’t be like this, cassettes spread out all over the floor. By the way, the one who was responsible for the copyright in Syria and the one who submitted the petition was Majed Zein Al Abdin. He was the head of the initiative. Yamen: Why? Did he have a production company? Rizan: No, he was a musician and an administrator in the Radio, Television & Music Department. He is one of the people who became a chairman of the committee and submitted it to the People’s Assembly, and it happened. As I said, for 5 to 6 months, everything was perfect, then things got out of hand. Yamen: After you were recording in the Zain Al Abdin studio in Damascus, what were your next steps and how did your career develop? Rizan: I’d work in the studios by day, and I went to play at the parties with Omar at night. We played numerous parties in Maraba (a Damascus suburb). This was around the time when Mark came to us and got to know us. I worked with Omar for 6 to 7 months in Maraba, but I didn’t like the atmosphere there. I told Omar I couldn’t work like that. You know why? Omar and I weren’t the same. Omar sings, finishes his concert, then sleeps till the next day. And the next day, after sleeping well, he goes to the next party. But I had to go to the recording studio in the daytime. When I go to those parties all night and then go to the studio, I can’t do anything! I mean, I’d emerge from that party atmosphere, then go to Mr. Majed – the man studied with Riyad Al Sunbati! When we’d try to talk about music after I came straight from Marbaa parties, I was distracted! I love to sit and benefit from the art as well. Yamen: Exactly. Rizan: Mr. Majed was an artist. I mean, he is a distinguished Riyad Al Sunbati graduate, I’m telling you! He studied in Cairo! You know what I mean? I’d go to those parties, where a drunk person comes up to you while you’re playing and asks you to do this and that. Once, a drunk person told me to bring him a glass of whiskey from the table while I was playing. When he came over, I looked at him thinking what is he on about?! I had to hold him and push him away. It happened while I was playing, so I started pressing the klaxon button with my hand and looking at the owner of the place. He started sending signals using a laser pen like this ... (demonstrates) Yamen: Ha ha ha! Rizan: He knew something had happened. After I finished, I told Omar that I wasn’t going to work there anymore. That was it. Yamen: You’d had enough. Rizan: I had to fight with people man! That’s not my job! You’d see people with no manners fighting, and then this woman starts to cuss at people, and that man curses…. Then the next day, I’m expected to go to sit with Mr. Majid at work. I mean, look at the contradiction. I had contradicting jobs I couldn’t follow. Yamen: And how did you then continue? When you left Maraba, what then? Rizan: I left Maraba and kept working with Mr. Majed. I had work there, making shaabi songs. Then after a while, I noticed that Omar was bored with his work as well. He said, “Wallah, Rizan I also won’t work there anymore either.” When I asked why, he said “There are a few famous songs in Maraba, but I don’t want to sing these things, and my reputation will be affected badly as a result. Rather than leave it like that, I’d like to leave this job completely and go back to our hometown.” The lyrics sung there were something like: “the wind lifts… lifts the dress… When the wind lifted her dress, and showed the number of her ‘motor’…” He told me, “How can I recite these words, brother? I’m too embarrassed to do it. If I sing this song for a day, two, three, four, it will become famous, and my reputation might be affected badly.” In Maraba there is no respect, no manners, you know what I mean? So he left there as well. Yamen: What year was this? Rizan: This happened at the end of 2006, after Mark had met us and began making an Omar compilation from his cassettes. Yamen: But this was still before you recorded with Mark and travelled to Britain? Rizan: Mark came and made an agreement to work with Omar’s previous music from cassette albums he had. He got his permission and told Omar to wait for a year or a year and a half to see results, and that they’d come back for him. So Omar took the money for that, put it in his pocket and said, “There’s no way he’ll come back. Forget it. Travelling, signing a contract...” He didn’t believe it. Yamen: What didn’t he believe? Rizan: He didn’t believe… Yamen: He thought Mark was lying to him? Rizan: No, he didn’t say he was lying to him. He thought it must be all talk and no walk. Yamen: Got you. He didn’t take him seriously. Rizan: Yes, he didn’t take him seriously. He thought that things wouldn’t go smoothly. Mark didn’t say that he was going to sign a contract immediately. He told him “I am getting authorisation for your songs to try and start a project. If it succeeds and we can work things out for you out there, wait for us for a year, year and a half maximum and we’ll come back for a visit to discuss.” Yamen: Okay. Rizan: So Omar said, “It won’t happen. Okay he took the music, but it won’t happen.” Afterwards, Omar and I went back to the Jazeera region. I built a full functional studio. Mr. Majid gifted me a few pieces, Vahe gifted me a few pieces and I made a studio in Ras Al Ain. I started working with artists in Ras Al Ain this time, as I had previously. And Omar and I went back to playing parties in the area, wedding ceremonies. Until we got that phone call from Mark and Alan (Bishop, Sublime Frequencies) via Raed Yassin (a Beirut-based artist who was translating for Sublime Frequencies). One day Raed called us and told us that Mark and Alan would like to talk to us. And that is where it all began, and after that, Mark was in the picture, and we had our (overseas) concerts and travelled. This is what happened. Yamen: Okay, so at this time you returned to the Jazeera region, you went back to Ras Al Ain and you built a studio. You were saying that you played at wedding ceremonies and… Rizan: We went back to work like we had before we went to Damascus. We’d play wedding ceremonies. I was working on songs in my studio – not specifically for Omar. I worked for Kurdish artists, Arab artists, I worked for artists in Germany. For example, people would send me songs from afar and I’d work on them. Then Mark and Alan came, and we began working with them. Things got a bit more serious – we signed a contract with them and after they left, Omar and I started preparing for it. Yamen: For Britain and Europe, you mean? Rizan: That’s it. We started preparing and we said, that’s how it is now. We signed a contract for three years, maybe, I don’t know how long it was. That’s it, we had work to do and we had to make new songs because Mark said something important, which we liked to apply in our concerts as well. He told us, “Try and sing the old songs from back when Omar had just started. Because we’ve compiled a record that represents Omar’s early cassettes. Now, Omar should present something from these old albums when you are onstage overseas.” Yamen: Got it. Rizan: So Omar and I started working and reviving things we’d worked on 10 years ago, so that when we’d play a concert, we would do something new based on what Mark and Alan had done to promote us. For instance, we shouldn’t be singing some other kind of pop music, when Mark had released a different kind of sound. We had to present the older material based on what Mark had compiled from our repertoire. So we started working on it. Yamen: And how was the experience? Were you recording or…? Rizan: No, we weren’t recording. We agreed on going back to the older songs from our history when we’d play these western concerts. We played these old songs and I went back to my old interludes, because I noticed that Mark had memorized everything! Mark attended a wedding with us and he knew exactly what I was going to play when. So we started practising, and when the time for concerts came, we were ready. When we were on the stage, Mark heard the old Omar from back in the days when he used to give his cassettes away as gifts. Yamen: Personally, how was your experience the first time you travelled to Britain? Rizan: Back then, I had already travelled twice outside of Syria. I used to go to Nowruz parties with a Kurdish singer. I was almost used to it. It was a bit new for Omar, but he is a person who can adapt fast. After the first two UK concerts, he was fine. He got used to it. He got the hang of it. Yamen: Ok. Then we know the rest of Omar’s story… Rizan: Yes. He eventually started working with new management and performing for more techno-oriented festivals. I stopped working with this management after four years in 2015 due to artistic differences, and Omar continued alone. Then Raed Yassin contacted me. he had previously recorded me playing dabke and some other material at a studio session in Lebanon in 2011. He told me, “I recorded that whole album of you playing dabke and other material, and I want to release that album. I’ll send you a paper to sign. If I can’t elevate you like Omar and have you playing keyboard solo on stage within a year, my name won’t be Raed anymore.” This happened in 2015, and my first solo album was released in 2015! Raed asked Mark to write my biography for the album liner notes, because he knew my history well. Six or seven months after the album was released, I got three offers to play solo at different festivals. One in Italy, one in France and one in Portugal. Back then, festivals would call Raed and he would negotiate for me. Onstage at a festival in the Netherlands, the audience loved the music so much that I was approached by a Dutch agency, who were managing two other bands at the festival. They asked if I had a contract with anyone else, brought a translator, and now I work with them for booking shows. But now it’s not like it used to be, after Coronavirus. Yamen: After the first record you made with Raed, you made another one right? Rizan: Yeah, I made another record in 2019, but with my bad luck, it hit the market the same day Ras Al Ain was bombed in 2019 – the day we fled the city. I even forgot about the record because of this. I mean, you know when you make a comeback, your friends share it, you share it in places, make some publicity. I did nothing of that sort. The company even wrote to me telling me that the record had been released and asking why my friends and I weren’t sharing it on our social media. I told them about the situation we were in. I also made a solo for a track by the band Acid Arab. They wanted to release the song on the same day as well. They asked me about the situation because they were watching the news. I told them how it was, and they asked if we had fled the city. I said yes. They told me that they would title the track “Ras Al Ain.” And that’s how it happened. Now if you google “Rizan Ras Al Ain”, Acid Arab’s music will appear in the search. That’s what happened, my friend. Yamen: Which company made the second Rizan solo record? Rizan: Akuphone. Mark did the mastering and he coordinated between us. Yamen: This happened in 2019, what’s next? You’re now living in Sweden, and you are working on your another record, aren’t you? Rizan: Yeah, now I live in Sweden. I am working on my third record. I mean I am getting ready in a better way. Covid was a difficult time for everyone because we stopped working, but we learned a lot, my friend. I have a lot of ideas in mind, for example. Yamen: What did you learn? Rizan: I listened, and I tried to absorb as much as possible. Learning how to develop something new and different to what other artists are doing now, for example. I want to make progress with whatever I am doing, something that stands apart from current releases. For example, to make something new in a song, something fresh that no one’s used before, or something with a classic feeling. Things like that. When you have a lot of free time, you start to think about what you want to do, what you want to produce. The next song I am arranging for Omar will be different. The style is going to be different from all the other songs on the market. Style-wise, work-wise and production-wise. Yamen: Is it going to be a single or will he add it to his album? Rizan: No, this is going to be a single. A while ago I recorded a song and included only a part of his voice. The song I am working on now has his voice with a choir. I’ll give him this song and he’ll record it and make a video clip. I want to gift him the song. I produced one ten days ago. This will be for his own personal benefit. Yamen: Thank you so much, Rizan. This interview has really been fascinating. Rizan: You are most welcome. Yamen: We’ll keep in touch. Thank you so much and thank you for your time. Best wishes. Rizan: Best wishes. Hala, hala – goodbye.